Glioblastoma

OncoSynergy was founded in 2011 to address glioblastoma. Despite technological advances and hundreds of millions of research dollars spent, overall survival from this highly aggressive primary brain cancer has not improved in decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

WHAT IS GLIOBLASTOMA?

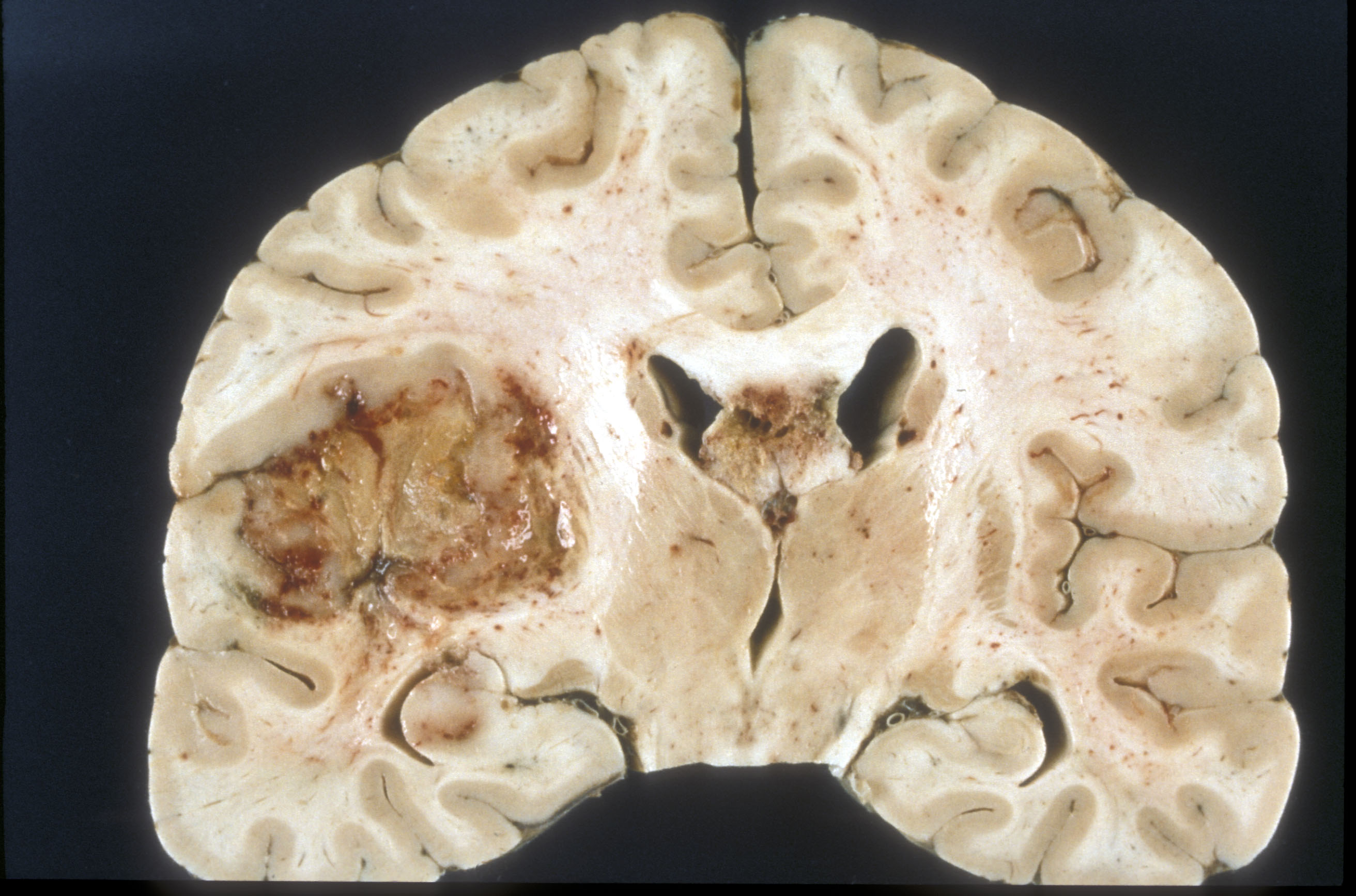

Gliomas are a type of cancer arising from the brain (i.e., primary brain tumor). Glioblastoma (also referred to as glioblastoma multiforme or GBM) is the most common and most malignant glioma. (Figure 1.)

Source: Wikimedia.org Credit: Sbrandner

WHERE DO GLIOBLASTOMAS COME FROM?

Glioblastomas are thought to arise from support cells of the brain called astrocytes or their progenitors (e.g., stem cells). Astrocytes play important structural and functional roles throughout the brain, such as maintaining the blood brain barrier, and are also involved in the healing process after brain injury.

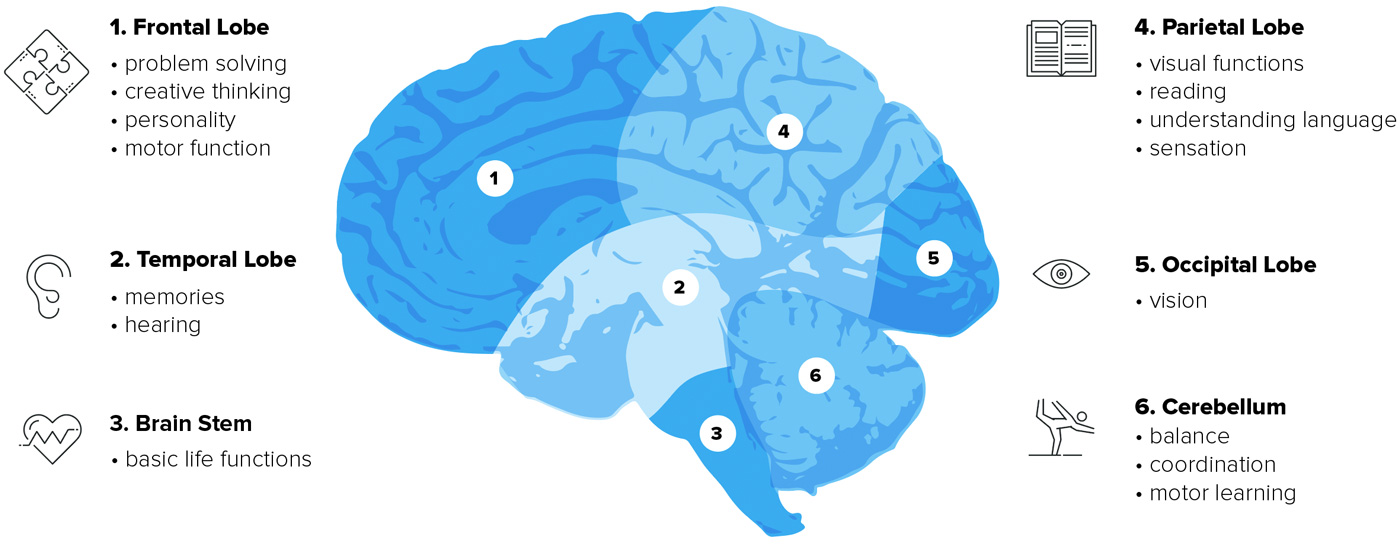

Glioblastomas are typically located in the more superficial cerebral hemispheres of the brain and only rarely in the cerebellum or deeper areas such as the brainstem. Although glioblastoma cells have a propensity to migrate large distances from the original tumor within the brain, they very rarely spread or metastasize elsewhere in the body.

HOW COMMON IS GLIOBLASTOMA?

Approximately 12,000 new cases of glioblastoma will be diagnosed in the United States in 2017 making it a rare cancer. Globally the incidence is approximately 3/100,000 people. Although glioblastoma can occur at any age peak incidence is between 55 and 60 years of age. Incidence is also slightly higher in men than women, and in individuals of Caucasian and non-hispanic race.

For comparison, both lung and breast cancer, the two most common cancers overall, are each expected to affect over 200,000 people in the United States in 2017 according to the American Cancer Society.

WHAT CAUSES GLIOBLASTOMA?

The causes of glioblastoma are largely unknown. Most people with a primary brain tumor do not have any known risk factors. Those that have been identified include:

- Exposure to ionizing radiation: such as radiation therapy used to treat cancer or occupational radiation exposure

- Rare genetic disorders: Von-Hippel-Lindau, Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, Neurofibromatosis

Overall, there is currently very little evidence that brain cancers run in families.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF GLIOBLASTOMAS?

As a brain tumor grows it may interfere with the normal functions of the brain. The first symptoms noted are usually due to increased pressure placed on the brain, most commonly:

- Headache

- Seizures

- Memory loss

- Changes in behavior

Other symptoms may occur depending on the locations of the tumor (Figure 2).

HOW IS GLIOBLASTOMA DIAGNOSED?

There are three key steps to obtaining an accurate diagnosis:

- A thorough neurologic exam: along with obtaining a history of your symptoms, a doctor will check your vision, hearing, strength, coordination, reflexes, and speech to elicit clues if a certain part of the brain is affected.

- Diagnostic Imaging: Most commonly an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) with contrast dye is the imaging modality of choice. The contrast dye helps make the tumor more visible. MRI also helps determine size, location and may be used for pre-operative planning.

- Tissue Biopsy: A definitive diagnosis is made by examination of a patient’s tumor tissue under a microscope (i.e., histopathology). Neuropathologists look at the types and features of cells present, and for signs of tumor aggression such as proliferation rate and formation of new tumor vessels. In addition, special genetic tests may be completed to further characterize the tumor.

HOW ARE GLIOMAS GRADED? WHAT GRADE IS GLIOBLASTOMA?

The most commonly used system, from the World Health Organization (WHO), grades gliomas based on certain features that can be seen under a microscope (i.e., histopathology, as above). Gliomas that arise from astrocytes (i.e., astrocytomas) are graded I-IV, with grade IV having the worst prognosis. Glioblastomas are designated grade IV astrocytomas because they exhibit the most aggressive histopathologic characteristics. Grade III and IV tumors are often lumped together under the term “high grade gliomas (HGGs),”

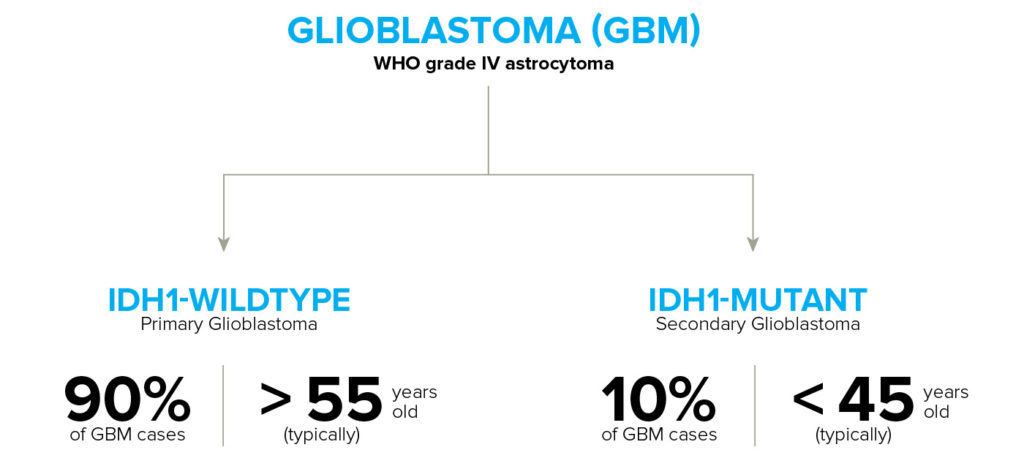

Also of importance is the fact that glioblastomas may arise as the first diagnosis (primary glioblastomas) or can arise after diagnosis with a lower grade astrocytoma. Those that arise when lower grade gliomas progress are referred to as secondary gliomas.

In 2016, the WHO included molecular and genetic information in the classification of gliomas. This addition is important for both patient management and prognosis. One important example is IDH1 gene status. The IDH1 gene encodes an enzyme important in brain metabolism. Patients with low-grade gliomas (grade I, II) and secondary glioblastomas often have a mutation in the IDH1 gene (“IDH1-mutants”) when tissue samples of their tumor are analyzed via special tests. The lack of mutation is referred to as having IDH-wild type status. IDH1 status is important as patients with a mutation in the IDH1 gene have a better overall prognosis. See Figure 3.

HOW IS GLIOBLASTOMA TREATED?

The mainstay or standard of care treatment for glioblastoma (established in 2005 by a large study) is surgery followed by radiation and chemotherapy (also known as the Stupp protocol).

The goal of surgery is to obtain a maximum safe resection – removing as much of the tumor as possible without injuring normal surrounding brain needed for vital neurologic function. It is impossible to completely remove the tumor with surgery due to the invasive nature of glioblastoma (i.e., individual tumor cells invade the surrounding normal brain). Surgery is helpful to decrease symptoms, particularly those related to increased pressure in the brain, and typically improves quality of life. Moreover, studies have shown that removing greater than 98% of the tumor improves prognosis. Surgery is generally safe due to significant advancements in technology, particularly in neuro-navigation. Neurosurgeons use this technology much like a GPS to safely remove as much tumor as possible.

After the surgical wound is healed, radiation therapy can begin. Multiple sessions of standard external beam radiation therapy (XBRT) are delivered to the tumor site as well as a margin around the tumor to target those infiltrating tumor cells surgery cannot reach.

Temozolomide (TMZ) is the first line chemotherapy for treating glioblastoma. TMZ is generally administered everyday during radiation therapy for a period of six weeks. This is typically followed up with 6-12 months of additional TMZ following radiation. During this maintenance period, TMZ is only given for the first five days of each month.

Unfortunately, recurrence of glioblastoma is inevitable. There is no established standard of care for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Instead recurrence is typically managed on a case-by-case basis. Options for treatment include:

- Repeat surgery

- Radiation therapy (XBRT as described above, or Radiosurgery – specialized local radiation)

- Second line chemotherapy

- Tumor Treating Fields (TTF): a portable medical device. Electrodes are placed on the scalp of the patient to deliver low intensity alternating electrical fields. Although the device was originally approved for recurrent glioblastoma, in 2015 it was approved as an adjuvant therapy in combination with TMZ following standard of care chemotherapy and radiation.

- Clinical Trials to test new experimental therapies or combination therapies (links to more info below).

There are three second line chemotherapies approved for glioblastoma:

- Lomustine (Ceenu or CCNU)

- Carmustine wafers (GliadelTM or BCNU) – biodegradable discs or wafers infused with carmustine that are placed in the resection cavity following surgery

- Bevacizumab (AvastinTM)

Unfortunately none of these second line chemotherapies have significantly improved overall survival for patients with glioblastoma. Because of this, some physicians may recommend to use drugs off-label (i.e., drugs that are FDA approved for a different condition than glioblastoma) as second line chemotherapy. It is important to note that in most, if not all cases, off-label chemotherapy is not covered by insurance.

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSIS?

Despite medical advances the prognosis for patients with glioblastoma remains poor. The median survival for patients diagnosed with glioblastoma is approximately 15 months after standard of care therapy (i.e., Stupp protocol). The one, two, and 10-year survival rates are 37%, 5%, and 3% respectively.

There are certain factors that may predict a more favorable prognosis:

- MGMT-methylation status: tumors that exhibit methylation of the promoter for the MGMT gene (inactivating the gene) respond better to TMZ therapy and therefore have a longer predicted length of survival.

- Younger age at diagnosis

- IDH1-gene mutation

- >98% tumor resection

WHAT IS THE FUTURE FOR GLIOBLASTOMA TREATMENT?

Medical research is the key to improving outcomes and the standard of care. Currently, there are nearly 400 clinical trials that are enrolling or are currently active for glioblastoma.

For information on our currently active clinical trial please visit ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z,Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). S Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence – SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2014 Sub (1973-2014) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> – Linked To County Attributes – Total U.S., 1969-2012 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014, based on the November 2014 submission.

- Louis DN, et al. (2016) “The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary.” Acta Neuropathol.

- Greenberg, Mark S. Handbook of Neurosurgery Seventh Edition. New York: Thieme Publishers, 2010.

- Mrugala MM. (2013). “Advances and challenges in the treatment of glioblastoma: a clinician’s perspective.” Discov Med. 15(83):221-30.

- Ostrom, Quinn T. et al. “CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2008-2012.” Neuro-Oncology Suppl 4 (2015): iv1–iv62. PMC. Web. 13 Dec. 2017.

- Reuss DE, Mamatjan Y, Schrimpf D, Capper D, Hovestadt V, Kratz A, Sahm F, Koelsche C, Korshunov A, Olar A et al (2015) “IDH mutant diffuse and anaplastic astrocytomas have similar age at presentation and little difference in survival: a grading problem for WHO.” Acta Neuropathol 129:867–873

- Soda Y1, Myskiw C, Rommel A, Verma IM. (2013). “Mechanisms of neovascularization and resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies in glioblastoma multiforme.” J Mol Med (Berl). 91(4):439-48.

- Weller M, Cloughesy T, Perry JR, Wick W. (2013). “Standards of care for treatment of recurrent glioblastoma–are we there yet?” Neuro Oncol. 15(1):4-27